Rashomon Christian Review

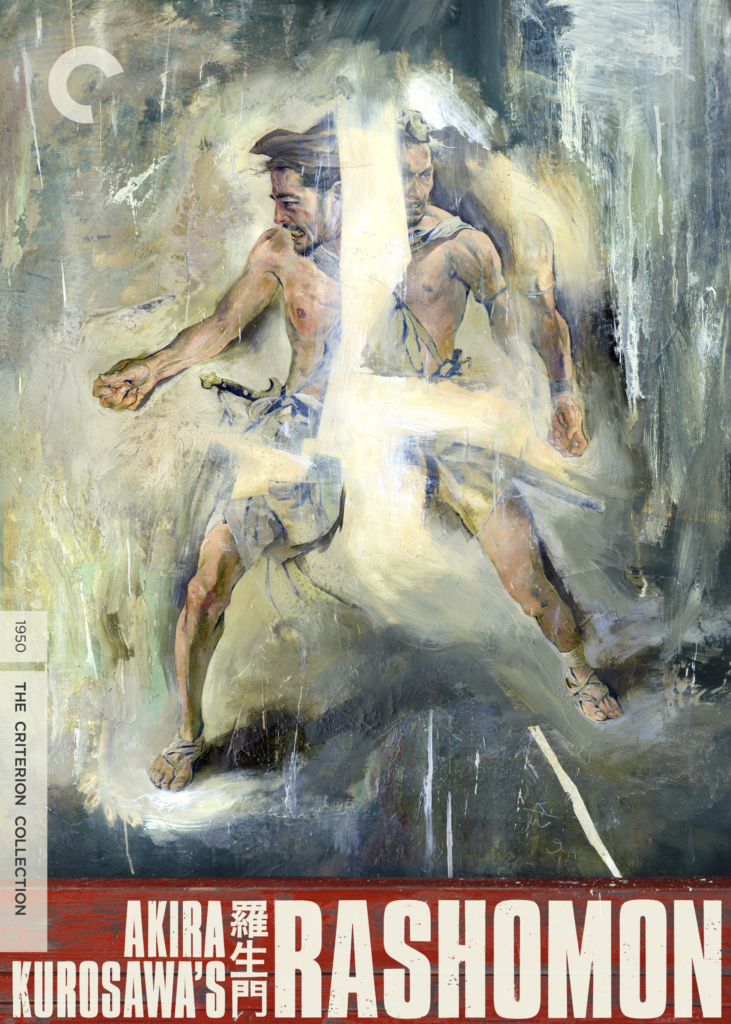

There are movies that entertain, some that inspire, and a rare few that shake the very foundation of how we see the world. Rashomon is one of those films. Directed by Akira Kurosawa in 1950, it’s not just a movie, but a haunting, vivid exploration of the human psyche. It’s a classic in every sense—richly layered, visually groundbreaking, and thematically complex, wrapping viewers in an enigmatic web of intrigue that leaves us questioning everything we think we know about truth and reality. But to call Rashomon merely a “classic” feels almost reductive. It’s more like an experience, one that unfolds in such unexpected ways that by the end, you feel as if you’ve been turned inside out, left pondering the messiness of human nature and the elusive nature of objective truth.

A Story Without a Center: The Many Faces of Truth

If you were to try to describe the plot of Rashomon to someone, you might find yourself at a bit of a loss. On the surface, it’s deceptively straightforward: a brutal crime has been committed—a samurai is dead, and his wife has been assaulted by a notorious bandit. The incident is recounted through four different perspectives—the bandit, the wife, the dead samurai himself (via a medium), and a humble woodcutter who stumbled onto the scene. But the devil is in the details, and here, those details don’t add up.

Each character tells a story that is dramatically different from the others. The bandit brags about his conquest; the wife paints herself as a victim caught between two men; the samurai (speaking from beyond the grave) offers a narrative tinged with tragic heroism, while the woodcutter’s version—seemingly objective—has its own unsettling inconsistencies. In each telling, the core facts of the crime shift and distort like reflections in a funhouse mirror. Who’s lying? Who’s telling the truth? Or, more disturbingly, could all of them be lying? And what does that mean for us, the audience, sitting in the dark, trying desperately to piece together some kind of coherent narrative?

The brilliance of Rashomon is that it refuses to give us easy answers. Instead, it thrusts us into a moral and philosophical fog, leaving us to grope around for a truth that seems to slip further away the harder we grasp for it. It’s a film that makes you feel like you’re chasing shadows—just when you think you’ve pinned something down, it shifts again, reminding you how slippery and subjective reality can be.

Kurosawa’s Mastery: A Cinematic Revolution in Light and Shadow

So much of Rashomon’s power comes from Kurosawa’s visionary direction. He takes what could have been a stage-bound exercise in narrative trickery and transforms it into a cinematic ballet, a dance of light and shadow that is as expressive as the performances themselves. The setting—a rain-soaked, crumbling gate where a priest, a woodcutter, and a commoner discuss the case—becomes a visual metaphor for the crumbling nature of truth itself. And the forest, where the crime took place, is a character in its own right: dark, dense, and almost sentient, its trees bending and twisting like silent witnesses to human folly.

Kurosawa’s use of the camera was revolutionary for its time. He employs long, fluid takes that draw us deep into the psychological space of each character, and then abruptly cuts to jarring close-ups that feel almost voyeuristic, making us uncomfortably complicit in the storytelling. The light filtering through the leaves above is fragmented and fractured, casting sharp, shifting shadows across the actors’ faces—mirroring the fragmented, fractured nature of their stories. It’s as if Kurosawa is using the very tools of filmmaking to underscore his themes, turning the camera into a kind of visual lie detector that catches every flicker of doubt, every shifty glance, every bead of sweat.

And then there’s Toshiro Mifune, the electrifying star of the show. His portrayal of the bandit Tajômaru is nothing short of a tour de force—wild, primal, almost feral in its intensity. Mifune doesn’t just act; he embodies the character, snarling and strutting like a caged animal, his every movement radiating raw, unpredictable energy. It’s a performance that grabs you by the throat and doesn’t let go, a perfect complement to the film’s chaotic, kinetic style.

A Story of Sin and Self-Deception: The Moral Quandary at Rashomon’s Heart

But for all its technical brilliance, Rashomon’s true genius lies in its thematic depth. It’s not just a story about a crime; it’s a story about the stories we tell ourselves. Each character isn’t just lying to others—they’re lying to themselves. They’re reshaping reality, subtly or overtly, to fit their own needs, their own insecurities, their own sense of identity. The bandit sees himself as a dashing rogue, the wife as a tragic heroine, the samurai as a wronged nobleman, and the woodcutter as a neutral observer—each spinning a narrative that absolves them, that casts them in the best possible light.

For a Christian viewer, this is where the film hits hardest. The Bible is full of stories about self-deception and the human capacity for sin. Think of David, who convinced himself that taking Bathsheba was his right, or Peter, who swore up and down that he would never deny Christ—until the rooster crowed. Rashomon taps into this same universal truth: that we are all prone to twisting reality, to building up our own self-image, even at the expense of the actual truth. It’s a sobering reminder of just how deeply flawed and fragile our grasp on reality can be.

And yet, for all its bleakness, Rashomon isn’t entirely devoid of hope. The film ends with a quiet, almost tender moment of grace—a small act of kindness that suggests that even in a world of lies and deception, goodness is still possible. It’s a glimmer of light in an otherwise dark landscape, a reminder that while we may never fully know the truth, we can still strive to act with integrity and compassion.

The Rashomon Effect: Still Shaping Culture Today

One of the most remarkable things about Rashomon is how deeply it has permeated our cultural consciousness. The Rashomon Effect—the idea that different people can have radically different perceptions of the same event—has become a staple not just of psychology, but of storytelling itself. You see it in everything from courtroom dramas to political debates to psychological thrillers. It’s a concept that feels eerily relevant in our current age of “alternative facts” and polarized perspectives. We live in a world where truth has become increasingly fragmented, where people retreat into their own echo chambers, each convinced that their version of reality is the only one that matters. Rashomon speaks to this modern dilemma with uncanny prescience, reminding us that truth is rarely simple, and that understanding often requires humility and empathy.

Final Verdict: A Masterpiece That Transcends Time and Culture

So where does Rashomon stand today? For me, it’s a nearly flawless film—a 9.5 out of 10. It’s a movie that challenges, provokes, and ultimately, transforms. It’s a movie that refuses to spoon-feed you answers, forcing you to wrestle with its questions long after the credits roll. It’s a movie that shows us the worst of humanity, but also hints at the possibility of redemption. It’s a movie that, even after multiple viewings, still has the power to surprise and unsettle. And that, in the end, is what makes it a true masterpiece.