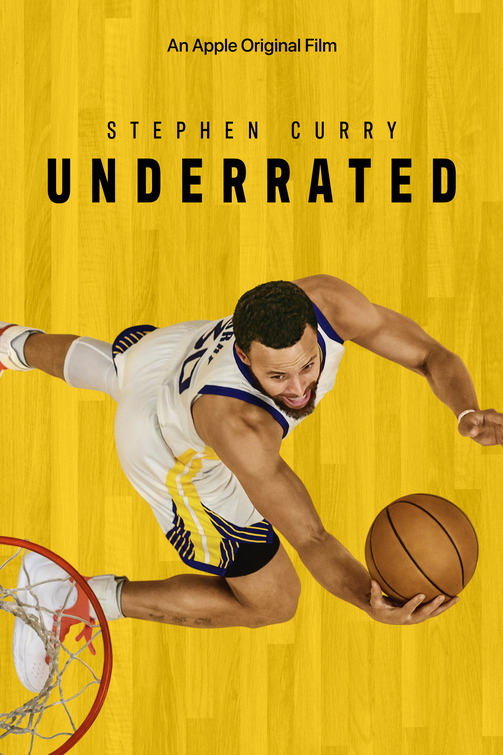

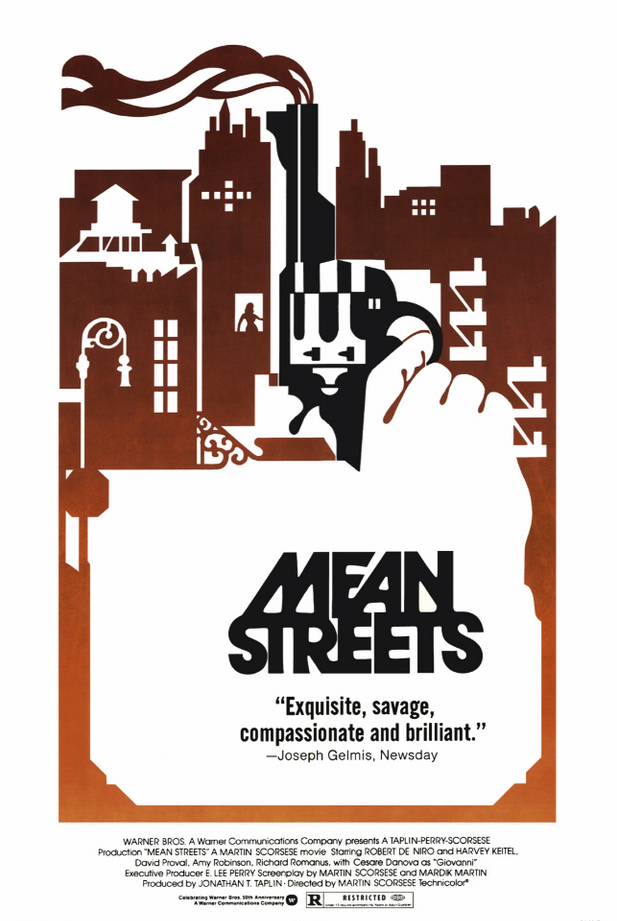

Mean Streets Christian Review

Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets—what can be said that hasn’t already been spilled across decades of reviews, essays, and retrospectives? It’s not your typical gangster flick, and that’s putting it lightly. No glamorous mafioso sitting on a leather chair pontificating over loyalty and honor. No guns blazing in some operatic, slow-motion ballet. This is something messier, something almost uncomfortably close. It’s like looking at a snapshot of a life caught between heaven and hell, where no choice is clean and redemption feels like a dream deferred. So why should Christians care? Why sit through the barrage of profanity, violence, and a moral murkiness that never really resolves itself? That’s what we’ll get into.

A Different Kind of Mob Story

This isn’t a film about organized crime the way we’re used to seeing it. Scorsese’s camera doesn’t take a step back to capture the grandiosity of the Mafia’s reach. Instead, it drops you right in the muck, up close and personal, with low-level thugs and wannabe wise guys. The heart of the story beats around Charlie (Harvey Keitel), a small-time hood trying to be a “good guy” in a bad world. Good—what does that even mean in a place like this? In Charlie’s case, it’s a slippery thing, a mix of guilt, obligation, and a warped sense of righteousness. He goes to church, he prays, he even tries to counsel his wild, self-destructive friend Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro), but he’s still collecting debts, still breaking kneecaps when the situation calls for it.

It’s not your typical hero’s journey. There’s no straight path to redemption, no real turning point where Charlie decides, once and for all, to choose the light over the darkness. Instead, he’s mired in the middle, always caught between trying to be better and giving in to the pressures around him. There’s a truth to that, though, a kind of realism that hits hard because life isn’t neat like that. People don’t just change overnight. And sometimes the battle between right and wrong isn’t fought on some grand stage but in the everyday decisions we make, minute by minute, moment by moment.

A Struggle for Sainthood

If you dig into the heart of Mean Streets, it’s really about faith—twisted, struggling, desperate faith. Scorsese, with his Catholic upbringing, weaves in religious imagery with a deft hand. There’s Charlie, lighting candles in the church, trying to scrub away his sins through ritual, hoping that by making all the right gestures he can somehow cleanse himself of the filth that keeps sticking to him. But he’s no saint. He’s a hypocrite, a liar, a man who wants to do good but can’t quite break away from doing bad. The whole film is a sort of meditation on Romans 7:19: “For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing.” That’s Charlie, right there. Torn between the world and whatever whisper of grace still haunts his conscience.

But it’s more than that, isn’t it? There’s an absurdity to his striving, a tragic comedy in the way he tries to play both sides, balancing his life in the gutter with his attempts to be a decent person. He’s not seeking God’s approval so much as he’s looking to ease his own guilt, to find a way to justify himself while still running with the same rough crowd. That’s where the heartbreak lies. He’s lost, caught in the lie that you can be good and bad at the same time. That you can live a life of sin and somehow pay it off in penance.

The Johnny Boy Problem

And then there’s Johnny Boy—played with chaotic brilliance by a young De Niro. He’s a force of nature, a walking disaster, the guy who always bets big and never cares about the consequences. He’s like the devil on Charlie’s shoulder, the living embodiment of everything reckless and self-destructive in their world. But he’s also Charlie’s friend, and that’s what complicates things. Loyalty, obligation—these aren’t just buzzwords for Charlie. They’re part of his twisted code. He sees himself as Johnny Boy’s protector, his savior. But Johnny doesn’t want saving. He mocks Charlie’s efforts, blows off his warnings, and seems almost to enjoy dragging them both further into the mess they’ve made.

Watching Charlie deal with Johnny is painful because you see the futility of it. Johnny doesn’t change. He doesn’t repent. He doesn’t even acknowledge that there’s something wrong with the way he’s living. He’s a man with no moral compass, no guilt, no shame. And yet, Charlie clings to him, convinced that somehow he can pull Johnny back from the brink. It’s the tragedy of thinking you can save someone who doesn’t want to be saved. It’s pride, in a way—a belief that you can be the one to fix what’s broken, that you can play God in someone else’s life.

The Use of Style: Scorsese’s Gritty, Jazz-Like Chaos

On a purely cinematic level, Mean Streets is a masterclass in style. Scorsese doesn’t just show you this world; he throws you into it, spins you around, and then drops you right in the middle of the madness. The camera moves with a restless energy, darting and diving, almost as if it’s mimicking the frenetic pulse of the characters’ lives. The street scenes are chaotic, alive with a sense of urgency that keeps you on edge. It’s like jazz—improvisational, unpredictable, full of wild, jagged rhythms.

And the music! Scorsese’s use of pop and rock tracks is revolutionary here. Songs don’t just play in the background; they comment on the action, set the mood, become a kind of Greek chorus that underscores the madness of it all. When Johnny Boy struts into a bar to the sound of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” you feel the swagger, the reckless confidence, the ticking time bomb that he’s become. It’s electric, a kind of visual and auditory overload that makes the film feel almost alive.

Redemption? Maybe, Maybe Not

So, what do we take away from a film like this? It’s easy to dismiss Mean Streets as nihilistic, a story without hope, without redemption. But that’s not quite right. There’s something in Charlie’s struggle, in his desire—however flawed—to be better, to do something good, that resonates. He never gets there, of course. The film ends on a note of violence and despair, with no neat resolution, no clear path to grace. But maybe that’s the point. Maybe Mean Streets is about the longing for redemption, the hunger for grace that we all feel, even if we can’t articulate it.

For Christians, there’s something deeply relatable in Charlie’s flawed humanity. He’s a man who wants to be more than he is but keeps falling short. He’s a sinner, but he’s not entirely given over to sin. There’s still a flicker of something good in him, something worth saving, even if he never finds it himself. In a world as brutal and unforgiving as the one Scorsese depicts, maybe that flicker is enough.

Final Thoughts and Rating: 7/10

In the end, Mean Streets isn’t a film for everyone. It’s rough, unpolished, and relentless in its portrayal of sin and struggle. But it’s also honest, deeply human, and—at times—achingly beautiful in its depiction of a man caught between the darkness and the light. For its raw power and its unflinching look at the complexity of faith, I’d give it a 7 out of 10. It’s not a story of triumph, but it’s a story worth telling—a story worth wrestling with, flaws and all.