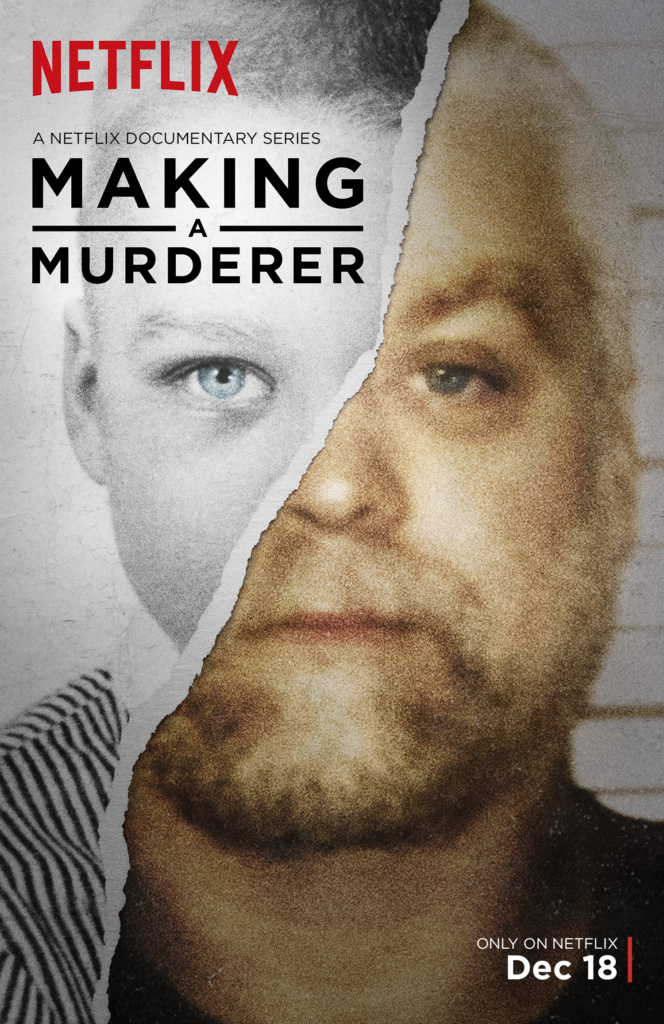

Making a Murderer Christian Review

You ever watch something that just leaves you feeling hollow, like you’re staring into the darkness of a deep, gaping hole? That’s kind of what Making a Murderer does. It pulls you into this maze of legal systems, corrupt police work, and human suffering, and by the time you’re done, you’re left with more questions than answers. The Netflix documentary series grabs you with its twisted tale of Steven Avery and his nephew, Brendan Dassey, but what keeps you glued to the screen is that nagging sense of, “What if justice isn’t what we think it is?”

For a Christian audience, this series brings up all kinds of issues about morality, justice, human fallibility, and, ultimately, the brokenness of this world. We know we live in a world where things go wrong. But when you’re watching someone’s life spiral out of control at the hands of a system that’s supposed to stand for justice, it cuts deeper. There’s a reason God cares so much about justice—it’s foundational to His character. So when we see a system twisted by corruption and incompetence, it leaves a mark.

A System Gone Awry: Justice Served or Justice Denied?

At the heart of Making a Murderer is this unnerving question: Did the system fail Steven Avery, or was it always broken to begin with? The show starts with Avery’s wrongful conviction in 1985. The guy was locked up for 18 years for a crime he didn’t commit. DNA evidence eventually sets him free, and just when it seems like he’s about to get some semblance of redemption, boom—he’s accused of another murder, the killing of Teresa Halbach.

And here’s where it gets messy. The documentary peels back the layers of how this case was handled, and none of it looks good. You’ve got sketchy police work, a prosecution that seems more focused on winning than on truth, and a defense team that’s swimming upstream in a sea of doubt and public opinion. Watching all this unfold, as Christians, we’re left thinking about the value of truth. What does it mean when a system designed to protect the innocent does the opposite? Proverbs 21:15 says, “When justice is done, it brings joy to the righteous.” But where’s the joy when truth seems buried under layers of deceit?

Steven Avery, Brendan Dassey, and the Powerlessness of the Vulnerable

If you’re looking for a story about triumph, Making a Murderer isn’t it. This is a story about broken people, caught in a broken system, where no one comes out unscathed. And honestly, the most heart-wrenching part of it all is Brendan Dassey. If you’ve seen the show, you know what I’m talking about. Brendan, Avery’s teenage nephew, gets roped into this mess, and the way his interrogation goes down is gut-wrenching. He’s this quiet, soft-spoken kid, clearly not equipped to handle the mental gymnastics the investigators are playing with him. They lead him in circles, feeding him information, pushing him into a confession that just doesn’t sit right. He’s confused, lost, and all he wants is to go home and watch wrestling.

Watching Brendan’s interrogation makes you feel helpless. It’s like watching a lamb being led to the slaughter, and the system—designed to protect—is doing the leading. There’s no one stepping in to say, “Hold on, something’s wrong here.” And maybe that’s the hardest part to watch. It’s easy to get angry, but deeper than that, there’s this ache for mercy, for someone to step in and speak truth into the situation. Jesus called us to care for the least of these, and Brendan, in all his vulnerability, is exactly that. He needed someone to be his voice, and instead, he was silenced.

The Elusiveness of Truth

The series presents this ongoing tension: What is truth? Everyone seems to have their version of it. The police believe one thing. The prosecution has its own narrative. The defense digs up another perspective. And us, as the audience? We’re stuck trying to figure out who’s telling the truth, or if it’s even possible to know the full story at all.

But truth isn’t relative. As Christians, we believe that truth is grounded in the very nature of God. Yet here, truth feels slippery, elusive, like it’s something that no one really wants to get to. It makes you think about the trial of Jesus, where Pilate famously asks, “What is truth?” (John 18:38). The irony there, of course, is that Truth was standing right in front of him, but Pilate didn’t recognize it. In Making a Murderer, truth feels buried beneath layers of power plays, human ego, and the desperate need for resolution—whether or not it’s the right one.

Complex Characters in a Broken World

The people involved in this story aren’t caricatures of good and evil. They’re human, flawed, and complicated. It’s easy to sympathize with Steven Avery—especially after the way the system failed him the first time. But as the show progresses, there’s always this question lingering: Did he actually do it? The documentary leans toward his innocence, but it never gives you a clean answer. And that’s frustrating.

Avery’s case forces us to reckon with the idea that even victims of injustice aren’t perfect. Romans 3:23 says, “For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” No one in this documentary comes off as pure, and that’s part of what makes it so unsettling. Avery’s a complicated figure. There’s evidence, there’s doubt, there’s a sense of being wronged, but also an undercurrent of “what if?” It’s a reminder that we live in a fallen world, where even those who have been wronged aren’t immune from sin and where the lines between victim and perpetrator sometimes blur.

The Heavy Weight of Injustice

At the end of the day, Making a Murderer isn’t really about one man’s guilt or innocence. It’s about the weight of injustice that hangs over our world. Watching this documentary, you’re forced to confront the reality that human systems—especially ones as critical as the justice system—are prone to failure. And that’s hard to swallow. It leaves you with that hollow feeling, like no matter what happens, justice was never truly served.

For Christians, this brokenness points us back to the hope of ultimate justice. We know that one day, everything that’s hidden will be revealed, and perfect justice will be done. Isaiah 30:18 says, “For the Lord is a God of justice; blessed are all who wait for him!” And maybe that’s the hope we cling to after watching something like Making a Murderer—the knowledge that this world’s brokenness isn’t the final word.

Final Thoughts: A Story that Lingers

So, where does this leave us? Making a Murderer doesn’t offer a clean resolution, and that’s part of its power. It’s raw, messy, and devastating, but it’s also a call to pay attention, to care about justice, and to be advocates for truth, especially for the vulnerable. It’s not easy viewing, but it’s important. For a Christian audience, it’s a reminder of the role we play in seeking justice and truth in a world that often seems indifferent to both.

The weight of injustice is heavy, but the call to pursue justice is clear. And maybe that’s what we take from this—an awareness of the brokenness around us, but also a renewed sense of purpose to act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with our God.