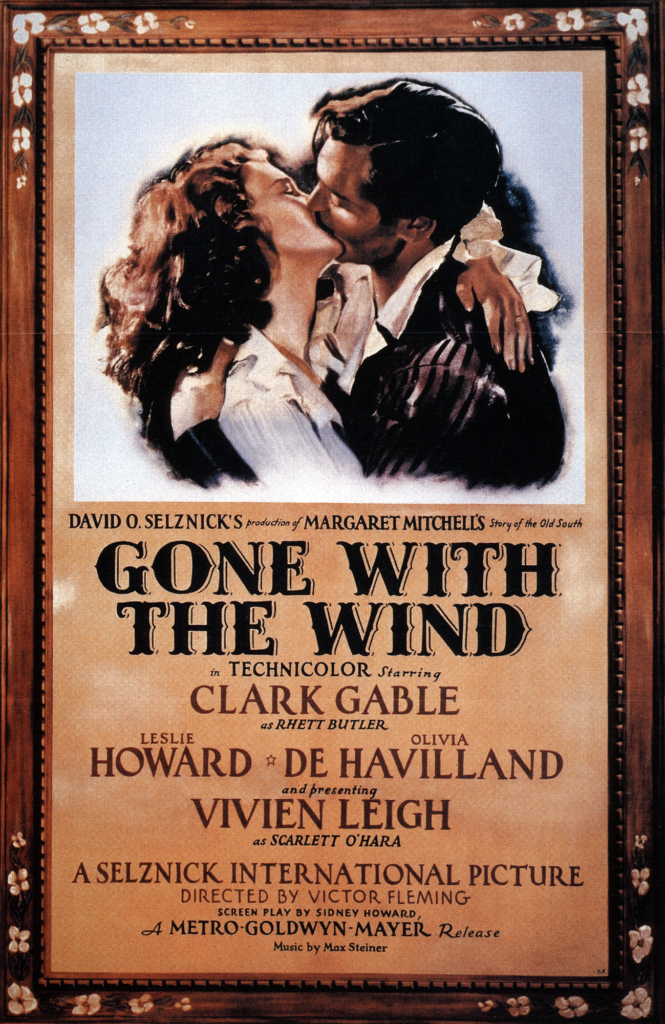

Gone with the Wind Christian Review

There’s no denying that Gone with the Wind is one of those films that defines Hollywood history. It’s grand, it’s sweeping, and it’s got that kind of old-school epic quality that few films today even attempt to capture. Released in 1939 and set against the backdrop of the Civil War and Reconstruction, it’s an adaptation of Margaret Mitchell’s novel that mesmerized audiences and still holds sway over cinema lovers. But, coming to it with a Christian lens, especially in today’s world, makes the experience more complex. There’s beauty to admire, but also unsettling elements that can’t be ignored, and that’s where the tension lies.

A Technicolor Triumph: Visual Storytelling at Its Peak

Let’s start with the obvious: the film’s visual craftsmanship is still astounding, especially in this recent restoration. The lush Technicolor is what makes Gone with the Wind leap off the screen, and that’s no exaggeration. It’s not just the big, jaw-dropping moments like the burning of Atlanta or Scarlett O’Hara’s red velvet dress; it’s the subtle things—the way Vivien Leigh’s complexion practically glows on screen, the almost painterly details in the costumes and sets. Watching it today is like stepping into a time machine that somehow makes the past feel vivid and alive.

For the Christian viewer, it’s hard not to appreciate the sheer creativity and artistry involved here. There’s something deeply reflective of human potential in seeing a work of art come together like this. Leigh’s performance as Scarlett O’Hara, for example, captures the complexities of human emotion in ways that still resonate. Her portrayal of a woman caught between desperation and determination is powerful, even if the character’s choices are often morally questionable. The care put into making this film is nothing short of extraordinary, a testament to the talent and vision of the artists behind it. In many ways, it showcases the kind of craftsmanship that honors God’s gift of creativity to humanity, even if the story itself complicates that appreciation.

Scarlett O’Hara: Complex and Deeply Flawed

Scarlett O’Hara—what a character. She’s selfish, manipulative, proud, and entirely focused on her survival, often at the expense of others. Watching her claw her way through one crisis after another, you can’t help but be captivated by her sheer willpower, even as you cringe at her decisions. She’s the definition of someone who embodies worldly ambition—always thinking about how she can get ahead, how she can secure her future. And from a Christian standpoint, it’s hard not to see Scarlett’s journey as a cautionary tale about the dangers of living for yourself and chasing after material success at any cost.

Scarlett’s life revolves around her pursuit of things that don’t last: money, status, romance, and social position. She’s driven by desires that never seem to fill the emptiness inside her. Every time she gets what she wants, it turns to ash in her hands, whether it’s Ashley Wilkes or the plantation at Tara. And that’s the real tragedy of Scarlett O’Hara—she’s a person who never understands that true fulfillment can’t be found in things or people but in a deeper, more spiritual foundation. She’s a perfect example of what the Bible warns against when it talks about storing up treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy.

At the same time, there’s something undeniably human about her. Scarlett’s complexity makes her someone we can empathize with, even as we reject the choices she makes. We all know what it’s like to want something so badly that we’re willing to compromise our values to get it. Scarlett’s relentless drive, though misdirected, taps into that universal longing for security, for meaning. It’s just that she seeks it in all the wrong places.

A Distorted View of the South

Of course, no discussion of Gone with the Wind can skip over the way it portrays the antebellum South. And this is where things get really uncomfortable. The film is deeply romantic about the old Southern way of life, painting it with this golden, nostalgic brush that’s not only misleading but dangerous. It idealizes plantation life, making it seem like a world of grand houses, flowing gowns, and charming manners, while minimizing—if not outright ignoring—the brutal reality of slavery that underpinned it all.

For Christian viewers, this presents a serious problem. We’re called to love justice, and the film’s glossing over of slavery is a blatant denial of that justice. Slavery was an institution that dehumanized people created in the image of God, and any depiction of that era that ignores this truth is fundamentally flawed. It’s not just a historical inaccuracy; it’s a moral one.

Hattie McDaniel’s performance as Mammy is one of the high points of the film, and she became the first African American to win an Academy Award for it. But even this groundbreaking moment is fraught with complications. Mammy is portrayed as a loyal servant who seems content with her role, reinforcing stereotypes rather than challenging them. Yes, McDaniel’s talent shines through, but the character herself is part of the film’s problematic racial dynamics. It’s a bittersweet achievement, a moment of personal triumph for McDaniel that exists within a larger narrative that fails to reckon with the true horror of slavery.

The Absence of Redemption

For all of its four hours, Gone with the Wind doesn’t offer much in the way of redemption. Scarlett doesn’t change. If anything, by the end, she doubles down on her old ways, vowing to get Rhett Butler back after driving him away. There’s no grand moment of self-realization, no repentance, no arc that suggests she’s learned anything from the wreckage of her choices. This lack of redemption leaves a gaping hole for viewers who are used to stories of transformation and grace.

For Christians, this is perhaps the most disappointing part of Scarlett’s character arc. The Bible is full of stories of flawed, broken people who encounter God’s grace and are changed forever—stories where selfishness, greed, and pride are confronted and transformed. But here, Scarlett’s journey ends not in humility or repentance but in stubborn pride. She remains trapped in the same cycle of self-centered ambition that’s brought her nothing but misery.

And that’s not to say every story has to have a neatly packaged redemption arc, but it does mean that Scarlett’s story feels incomplete. There’s a lingering sense that she’s still searching for something, even if she doesn’t know it yet. As Christians, we know that the fulfillment Scarlett is looking for can’t be found in material wealth or romantic conquests. It’s found in a relationship with God, in living a life of love, sacrifice, and service. But Scarlett never takes that step, and the film doesn’t even hint at the possibility.

The Beauty and the Beast of It

In the end, Gone with the Wind is both beautiful and troubling. It’s a masterpiece of filmmaking, a triumph of artistry and craftsmanship that deserves its place in the cinematic canon. But it’s also a product of its time, steeped in a worldview that’s deeply problematic. As Christians, we can appreciate the beauty of the film’s artistry while also recognizing its moral flaws.

There’s a tension here, and it’s one that we can’t ignore. We’re called to engage with culture thoughtfully and critically, to seek out what is good and true while being honest about what is wrong. Gone with the Wind offers a powerful reminder that not all that glitters is gold and that sometimes, the stories we tell ourselves about the past are more comforting than true.

Final Verdict: 7/10

So, where does that leave us? For all its technical brilliance and emotional power, Gone with the Wind falls short in its portrayal of moral truth. It’s a film worth watching, but it requires discernment. It’s a 7 out of 10, a flawed masterpiece that’s both magnificent and unsettling, a reflection of both human creativity and human brokenness.