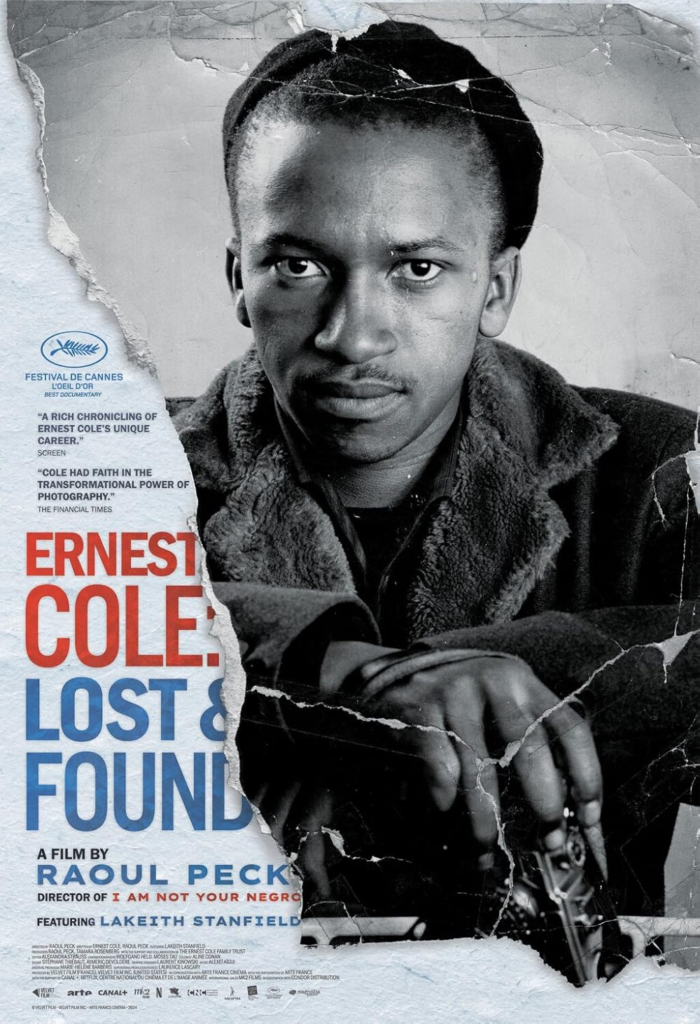

Ernest Cole: Lost and Found Christian Review

The moment you step into Ernest Cole: Lost and Found, you’re met with a sense of gravity. Raoul Peck doesn’t just tell a story; he weaves an atmosphere, inviting viewers to grapple with a life that was at once deeply ordinary and extraordinary. Ernest Cole, a South African photographer who captured the raw edges of apartheid, becomes more than an artist on-screen—he becomes a witness, a prophet of sorts, speaking truth to power. Peck’s film feels like a calling to reflect, to engage with something larger than ourselves.

The Art That Speaks Without Words

Art can whisper, shout, or sing, and Cole’s photographs seem to do all three. There’s a biblical weight to his images—snapshots of suffering, injustice, resilience. You can’t look away. Peck’s documentary underscores the depth of this visual storytelling. Cole’s lens wasn’t just a tool for capturing reality; it was an instrument for exposing it, much like the prophets of old laid bare the sins of their nations.

As a Christian viewer, it’s impossible not to draw parallels. Cole’s work reminds me of Micah’s call to “act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God.” He sought justice with every frame, depicting the humanity of the oppressed in a way that transcends time and geography. It’s not merely about apartheid-era South Africa; it’s about how we see the world and the people in it.

Homesick in a Broken World

The film lingers on Cole’s years in exile, an element of his life that feels particularly poignant. He left South Africa to escape the suffocating grip of apartheid but traded one kind of longing for another. In leaving, he gained freedom to share his work with the world, yet he lost the place that shaped him.

This tension—freedom at the cost of home—feels deeply spiritual. As Christians, we often talk about being sojourners in a foreign land, a concept echoed in Cole’s life. The ache of homesickness he carried, detailed so tenderly by Peck, mirrors the human condition. There’s a restlessness in all of us, a yearning for home that isn’t tied to geography but to something eternal. Watching this part of Cole’s story unfold, I couldn’t help but think of Jesus’s words in John 14:2: “I go to prepare a place for you.”

Cole’s wandering, his yearning, was for more than just the soil of South Africa—it was for belonging, for reconciliation. Isn’t that what we all crave?

Legacy and the Weight of Indifference

One of the most moving—and maddening—aspects of the film is the way it confronts Cole’s lack of recognition during his lifetime. He gave so much, risked so much, and was met with near silence. There’s a holy anger that rises up in you as you watch; how could the world ignore such a gift?

But here’s the challenge Peck seems to lay before us: how do we honor a legacy without reducing it to mere sentimentality? Cole deserves to be remembered, not just for his artistry but for his courage. And yet, reverence alone isn’t enough. Peck makes it clear that true tribute demands action. It’s not enough to admire the photos; we have to confront the systems of oppression they expose.

From a Christian perspective, this is convicting. How often do we, as the Church, pay lip service to justice without engaging in the messy work of making it a reality? Cole’s story is a reminder that faith without works is dead.

The Beauty of Brokenness

What struck me most about Lost and Found is how it holds space for both tragedy and hope. Cole’s life wasn’t neat. It didn’t tie up with a bow. There’s loss, betrayal, exile, and, ultimately, death in relative obscurity. And yet, Peck doesn’t leave us there. By the end of the film, you feel uplifted, not because the story is happy but because it’s true.

There’s a redemptive quality to truth, even when it’s hard. Watching Cole’s life unfold, I thought of the Apostle Paul, who spoke of being “poured out like a drink offering.” Cole gave everything, and though the world didn’t recognize it in his lifetime, his work lives on.

This tension—between brokenness and beauty, despair and hope—is the heartbeat of the Gospel. Jesus himself embodied it, bringing life out of death, hope out of hopelessness. Cole’s story, though not explicitly religious, echoes this rhythm.

A Film That Asks More Than It Answers

Peck’s documentary doesn’t tie things up neatly, and that’s part of its brilliance. It leaves you full—of emotion, of questions—yet somehow hungry for more. The narrative flows like a conversation rather than a lecture, inviting viewers to wrestle with the complexity of Cole’s life and work.

For Christians, this lack of resolution is an invitation. It’s a call to reflect on our own role in the ongoing story of justice and reconciliation. What are we doing to honor the legacies of those who have gone before us? How are we using our gifts to speak truth to power?

Peck doesn’t offer easy answers, but perhaps that’s the point. Faith, after all, isn’t about certainty; it’s about trust, about stepping into the unknown with hope.

A Closing Reflection

By the time the credits roll, you’re left with the feeling that Cole himself has spoken to you. His words, his images, his life—they linger, like the echo of a hymn. And isn’t that what great art does? It points beyond itself to something greater, something eternal.

As I think back on the film, I’m reminded of the words of Isaiah: “Learn to do good; seek justice, correct oppression; bring justice to the fatherless, plead the widow’s cause.” Cole’s life was a living embodiment of this charge. Peck’s documentary, in honoring him, challenges us to take up the mantle.

Rating: 9/10

Ernest Cole: Lost and Found isn’t just a film; it’s an experience. It’s a call to see, to feel, to act. For Christians, it’s a profound reminder of the power of truth, the beauty of brokenness, and the eternal hope we have in Christ. It’s not perfect, but maybe that’s fitting. After all, neither was Cole’s life. And yet, in its imperfection, it shines.