Bird Christian Review

Watching Andrea Arnold’s Bird is like plunging into a story that pulls no punches, a journey through broken lives held together by threads of resilience and moments of tenderness that catch you off guard. It’s intense, harrowing even, yet undeniably compassionate—a film that lives in the spaces between violence and love, hope and despair. For a Christian audience, Bird raises challenging questions about human dignity and grace, especially for those who seem to have been given very little of it by life.

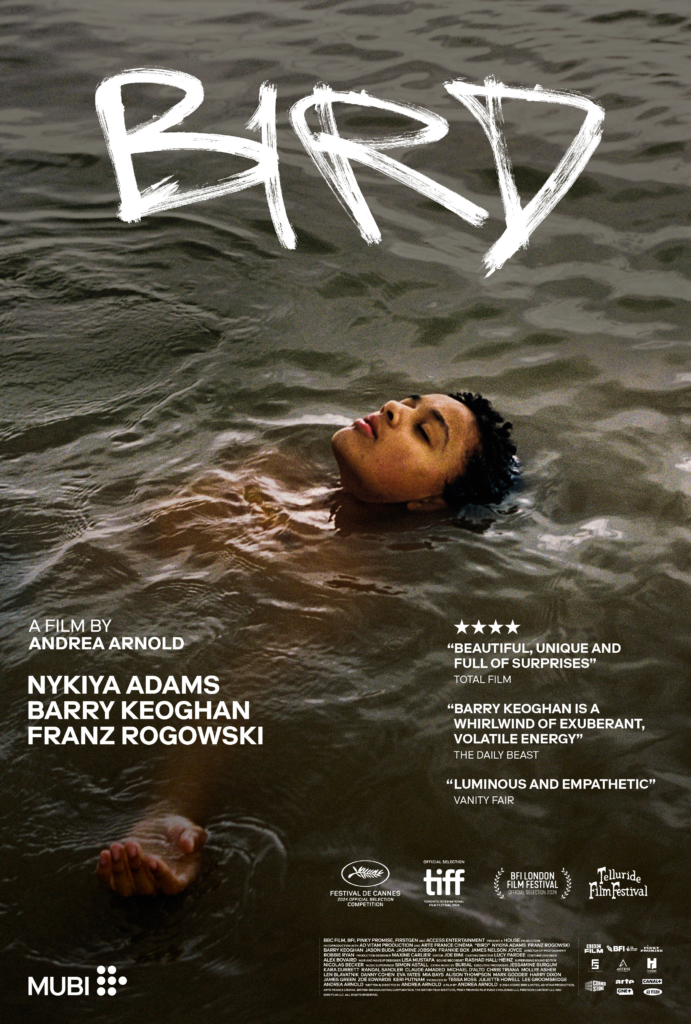

Bird centers on the life of Bailey, a young girl raised on the margins of society, entangled in cycles of poverty, neglect, and broken relationships. But Andrea Arnold doesn’t treat Bailey like a statistic. She’s a young girl who lives and breathes, who dreams and fights her way through life with a spirit that’s neither fully crushed nor entirely unscarred. Barry Keoghan plays her father, a chaotic, affectionate drug dealer, while Franz Rogowski’s character, the “bird-man,” is a mystical yet vulnerable presence, a source of imaginative hope for Bailey in an otherwise bleak world.

The Rough Edges of Life: Violence, Tenderness, and Faith in Humanity

Arnold doesn’t sanitize the world she’s created; she dives into it, capturing the grit and the grime, the unvarnished reality of life on the fringes. This is a story where violence isn’t just a backdrop; it’s a visceral part of the characters’ lives. There’s an underlying sense of danger, an awareness that nobody’s intentions are entirely pure and no adult is beyond reproach. For a Christian viewer, this might be unsettling. We’re shown people at their worst, people who have been failed and, in turn, are failing those around them.

Yet in the middle of all this harshness, there are glimmers of unexpected grace, of an unbreakable spirit that can’t quite be stamped out. Arnold’s world doesn’t look away from suffering, but she also doesn’t let it have the last word. It’s a strange, unsteady balance between optimism and bleakness, but it’s one that rings true, capturing the paradoxical nature of humanity. Bird shows us that even in the most chaotic, damaged environments, there are moments of beauty and acts of kindness that catch us off guard. These moments aren’t grand gestures or miraculous rescues, but small, quiet acts of care—a hug, a smile, an attempt to protect.

Beauty Amid the Broken: Cinematic Hope and the Spirit of the Phoenix

Arnold’s visual storytelling in Bird is nothing short of stunning. The film is a feast for the eyes, even as it tackles challenging subjects. The color palette is vivid—reds, whites, and blacks blend and clash, filling the screen with life, as though the camera itself were trying to revive the worn-out world it’s capturing. The edges of the image seem burnt, remade, like a phoenix rising out of ashes. For Christian viewers, this imagery speaks to something deeper, echoing the concept of resurrection and rebirth. The phoenix, that mythical bird rising from its own ashes, can feel like a stand-in for Bailey herself—struggling, beaten down, but still finding a way to rise again, to press on in the face of overwhelming odds.

The cinematography brings to mind the beauty of redemption, of finding light in dark places, even if it’s only a flicker. It’s as though Arnold is saying that there’s something sacred in survival, in simply being, despite the odds. The result is a kind of aesthetic spirituality, a reminder that beauty and dignity can be found even in lives that the world has disregarded. For people of faith, this might resonate as an echo of the divine spark, a reminder that every human soul has worth, regardless of circumstance.

Characters on the Fringes: Human Love and Divine Compassion

One of the most remarkable things about Bird is its commitment to showing the humanity of people who are often overlooked or dismissed. Keoghan’s character is a prime example of this. He’s not the kind of father you’d put on a pedestal—he’s a drug dealer, unreliable, and unpredictable. And yet, there’s something real and affectionate about him. He loves his daughter, however imperfectly, and that love matters, even if it doesn’t look like a storybook version of fatherhood.

For Christians, this portrayal might challenge conventional views on family and love. It’s messy, flawed, and fraught with mistakes, but there’s an authenticity there that makes it powerful. It’s a reminder that love, even when it’s imperfect, can still have meaning. We’re all broken people trying to love each other the best we can, and sometimes that means embracing people as they are, mess and all. In a way, Arnold’s film shows a kind of grace—a love that exists despite failure, a reflection of the way God loves us in our own brokenness.

Then there’s the “bird-man,” played by Rogowski, who adds a touch of magic to the film. He’s an unusual, almost mystical presence, and his relationship with Bailey takes on an air of mystery and innocence. He’s the character who brings hope, a reminder that even in the harshest realities, there’s room for imagination and creativity. It’s not a perfect answer to the struggles Bailey faces, but it’s something—a spark that keeps her going.

The Storybook Ending and the Reality of Hope

In a world that often seems entirely indifferent, Bird offers a glimmer of optimism. The film doesn’t end with a triumphant rescue or a miraculous turnaround, but it does end with a kind of quiet resilience. There’s a softness to it, a reminder that life, despite all its brutality, can still hold moments of tenderness and connection. It’s not a neat, storybook ending, but for Bailey, it’s enough.

Christian viewers might find this ending a bit open-ended, perhaps even incomplete. Bird doesn’t provide a straightforward narrative of redemption, and it doesn’t tie up all its loose ends. Instead, it leaves room for interpretation, inviting us to sit with the questions and to find our own meaning in the story. In a way, that’s part of the beauty of Arnold’s filmmaking—she respects her audience enough to let us wrestle with the ambiguity, to find hope in the unresolved.

Bird feels like an invitation to reflect on the nature of resilience and the quiet dignity of those who fight their way through life’s hardships. For people of faith, it’s a reminder that even the most broken lives are worth something, that even in the harshest environments, there’s room for grace.

Why Bird Stays with You

Arnold’s Bird isn’t a film you watch once and forget. It lingers, leaving you with images of Bailey and her world, with questions about how we view those on the margins and how we find beauty in the broken. It’s a film that speaks to the Christian call to care for the least of these, to look for the image of God in every person, even when the world has stripped them of their dignity.

This is not a film for everyone. It’s gritty, emotionally intense, and challenging. But for those willing to engage with it, Bird offers a perspective that’s both humanizing and hopeful. It reminds us that grace doesn’t always come in grand gestures; sometimes, it’s found in the quiet persistence of a young girl who refuses to give up, even when the odds are stacked against her.

In the end, Bird is more than just a film. It’s a reminder of the power of compassion, of the beauty that can be found in brokenness, and of the enduring hope that even the hardest lives hold within them the potential for something more. For a Christian audience, it’s a powerful meditation on faith, love, and the resilient spirit that reflects the image of God in every human soul.