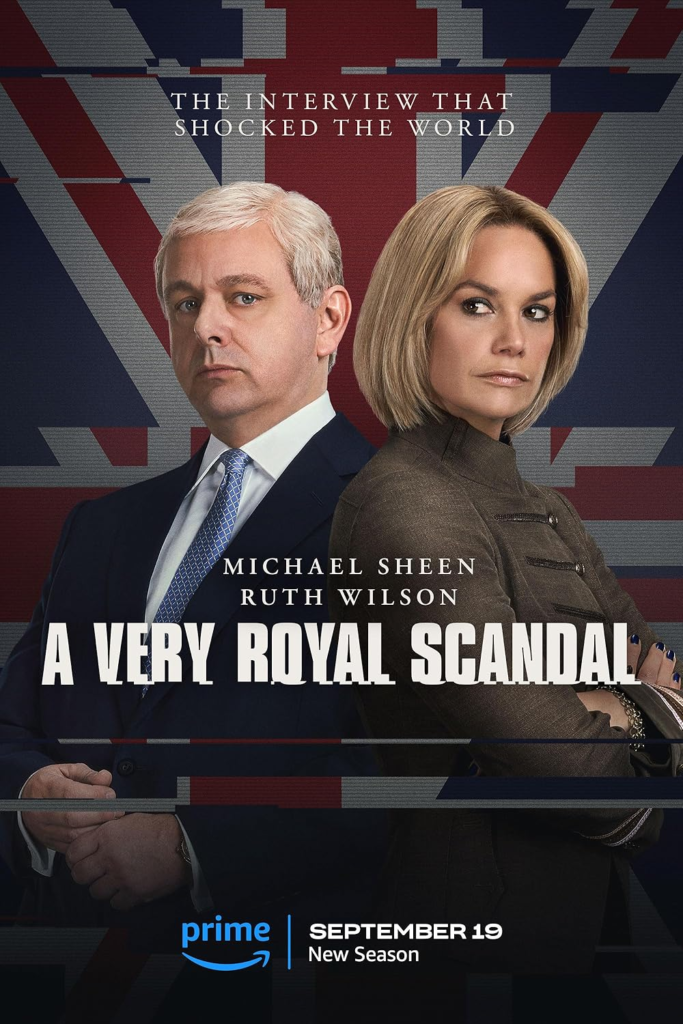

A Very Royal Scandal Christian Review

Royalty has this almost magnetic pull, doesn’t it? Even in a nation built on rebellion against the crown, Americans can’t seem to help themselves from peeking behind the palace curtains. And when it comes to “A Very Royal Scandal,” the allure is no different. Like a slow-motion car crash, we know the grim outcome, yet we can’t tear our eyes away from the wreckage as it unfolds. In just three episodes, this show dives deep into one of the most infamous interviews of the modern era, dredging up all the intrigue, the cringe, and, yes, the dark comedy of Prince Andrew’s catastrophic BBC appearance. But here’s the thing: the series goes beyond just the flashy headlines. It’s about reputation, morality, and the silent, shadowy consequences of scandal that echo long after the cameras stop rolling.

But don’t mistake this for just another royal expose. Sure, it’s got the opulent backdrops, the stern-faced courtiers, and the inevitable stiff-upper-lip moments, but there’s more beneath the polish. The show uses this singular moment—the infamous interview—to peel back the layers of privilege and power, and what we see isn’t so pretty. It’s a dark, glossy peek into the complexities of power dynamics, image manipulation, and the ethical dilemmas that swirl around those who report on them. In other words, “A Very Royal Scandal” wants to be more than just a guilty pleasure. But does it succeed?

Caught in the Crossfire: The Ethics of Exposing the Truth

First, let’s talk about Emily Maitlis, the journalist at the center of this maelstrom. Played with a sort of restless intensity by Ruth Wilson, she’s not your standard-issue heroic reporter. She’s not out to save the world, but she’s not trying to burn it down, either. There’s a weariness to her portrayal, a sense that Maitlis knows she’s caught in a machine much bigger than herself—a machine that chews up both the good and the bad. She’s a journalist, yes, but also a performer, aware of the power of perception, of how one raised eyebrow or softened tone can change the story.

For Christians, this moral complexity hits close to home. After all, how often do we weigh the cost of truth-telling? The Bible tells us to speak the truth in love, but there’s a tension here: what if the truth isn’t loving? What if speaking it might do more harm than good? The series doesn’t try to answer these questions, and that’s both its strength and its flaw. It leaves you to wrestle with it on your own.

Is Maitlis a hero, or just another cog in the relentless media machine? The show doesn’t lean too hard one way or the other. Instead, it presents her as a woman driven by a need to expose the truth but uncertain of what that truth will unleash. There’s no neat resolution, no clear-cut moral to take home, just the uncomfortable realization that sometimes truth, when revealed, can look more like a wrecking ball than a beam of light.

The Prince Unraveled: A Tale of Hubris and Denial

And then there’s Prince Andrew. Oh, Andrew. In Michael Sheen’s hands, the man is more than just a disgraced royal—he’s a study in self-delusion. He blunders through the series, oblivious to his own folly, convinced that his royal stature can shield him from the consequences of his actions. Sheen doesn’t play him as a one-note villain. There’s no sneering malice here. Instead, we get a portrait of a man so ensnared by his own privilege that he can’t see the snare tightening around him. You almost feel sorry for him. Almost.

But it’s not pity the show is after. Instead, “A Very Royal Scandal” seems to want us to consider how power can warp a person, how it can blind them to their own sin. There’s a tragic element here, but it’s not tragedy in the Shakespearean sense—it’s more banal, more pathetic. Andrew’s downfall isn’t the result of a grand moral failing but a series of small, almost laughable errors. It’s hubris, sure, but it’s also just plain stupidity. And that’s what makes it so fascinating.

The Bible says, “Pride goes before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall” (Proverbs 16:18), and Andrew is a textbook case. The problem is, there’s no real fall here, not in the sense of a soul brought low and made to repent. Instead, what we get is a man stumbling blindly into disgrace, with no moment of self-awareness, no cry of “I have sinned!” There’s no Davidic moment of contrition. Just a slow, awkward spiral downward, watched by the world, and by us, with a kind of grim satisfaction.

The Spectacle of Sin: Are We Just Voyeurs?

That brings us to the audience—us. Because let’s face it, part of the reason we watch these shows is the thrill of seeing someone else’s perfect world crumble. It’s that voyeuristic pull, the same one that keeps us scrolling through celebrity gossip or glued to courtroom drama. “A Very Royal Scandal” leans into this, aware of our complicity. We know we shouldn’t look, but we can’t help ourselves.

There’s a scene in the second episode where Maitlis sits across from Andrew, the two of them framed by the cold, sterile beauty of a royal drawing room. It’s almost clinical, the way she dissects him, probing gently at first, then more insistently as she realizes how deep his blindness goes. And we’re right there with her, leaning forward in our seats, waiting for the next crack in the facade. There’s something unsettling about that, something that should make us pause.

As Christians, it’s worth asking: why do we find these stories so compelling? Is it because they show us that even the mighty are flawed, just like us? Or is it because, deep down, we like watching them fall? There’s a line between righteous indignation and schadenfreude, and this show dances right on the edge of it. Maybe that’s why it leaves such a strange aftertaste. It’s not just about Andrew or Maitlis or the scandal—it’s about us and why we’re so drawn to the spectacle of sin.

A Hollow Victory: Entertainment Without Redemption

By the time the credits roll on the final episode, there’s no catharsis. The scandal has played out, reputations are in tatters, and the palace stands as cold and unyielding as ever. It’s great television, no doubt—sharp, well-acted, and surprisingly nuanced for what could have been a simple tabloid dramatization. But there’s a hollowness to it, a sense that we’ve just watched something bleak and empty, without any redemptive arc to balance the darkness.

For Christians, that lack of redemption is hard to swallow. We believe in a God who brings light out of darkness, who redeems even the most shattered lives. But here, there’s no grace, no forgiveness, no hope. Just a slow unraveling, watched with grim fascination by a world hungry for more.

Rating: 6/10

Watch it if you’re curious, but be aware: this isn’t a story that will uplift or inspire. It’s a polished portrayal of moral failure and the power of perception, but it ultimately leaves you cold. For all its nuance and complexity, “A Very Royal Scandal” is, at its heart, a tragedy without a hint of hope. And maybe that’s the real scandal.